Improved domestic and global conditions are expected to raise sub-Saharan Africa’s growth rate next year.

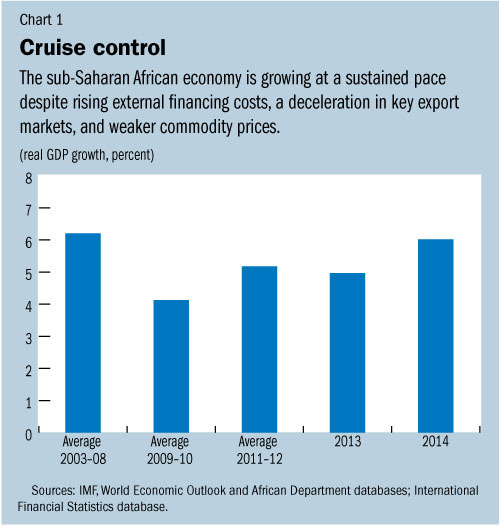

The IMF’s latest Regional Economic Outlook for sub-Saharan Africa projects an acceleration of GDP growth to 6 percent in 2014 from around 5 percent in 2013 that will be strongest among oil exporting and low-income countries.

The report notes that the sub-Saharan African economy continues to grow at a sustained pace despite rising external financing costs, a deceleration in key export markets, and weaker commodity prices (see Chart 1).

Regional output will expand by about 5 percent in 2013—more rapidly than in 70 percent of the countries in the world—as a result of continuing investment in infrastructure and productive capacity. In 2014, real GDP growth is expected to accelerate to 6 percent, favored by improved global and domestic conditions.

Growth projections for 2013 have been adjusted downward compared to those of May 2013, reflecting less favorable global conditions and some domestic headwinds, such as anemic private investment and consumption in South Africa, delays in budget execution in Angola, and oil theft in Nigeria. However, the magnitude of this revision is modest.

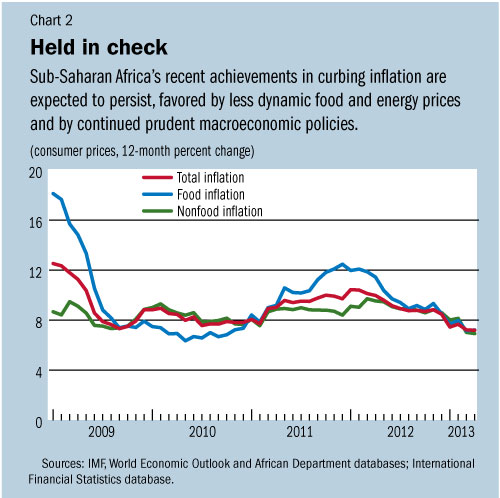

Recent achievements in curbing inflation—projected to average 6.9 percent in 2013—are expected to persist, favored by less dynamic food and energy prices and by the maintenance of prudent macroeconomic policies (see Chart 2). Nevertheless, some countries that continue to experience a rapid increase in prices will need to continue their efforts to keep inflation under control, the outlook says.

Elevated fiscal deficits

Fiscal deficits remain elevated and are set to widen in many countries, partly as a result of weakening revenues—most notably among oil exporters—and ambitious public investment programs. However, government debt appears sustainable in most countries, following a decade of strong growth and, among many low-income countries, debt relief as well.

The report notes that external current account deficits have widened significantly since the global financial crisis, reflecting higher investment and, to a lesser degree, lower saving, and have been financed to a large extent by foreign direct investment flows.

Given this mix of financing, these deficits have generally not raised indebtedness, and the risks they carry have more to do with the eventual return of the underlying investments than with a sudden interruption in financing. Current account deficits are projected to narrow in the medium term, as investments mature and export capacity rises, but will remain significant in some countries.

Downside risks

The main risks to this outlook originate from external factors. A further deceleration in global growth, especially in China and other emerging economies, could weaken demand for sub-Saharan African exports. Slower world growth could also affect commodity prices and might result in lower foreign direct investment if certain export oriented projects were reassessed. Aid flows might also be reduced, although energy importers could benefit from lower oil prices.

Detailed simulations of relatively large but still plausible shocks to commodity prices suggest that growth in the region would be affected moderately, although some countries depending on a few mineral products could be affected significantly.

A tightening of global monetary conditions, which could be prompted by the transition of U.S. monetary policy toward more normal conditions, could lead to a reversal of private financial flows and a general tightening of financing conditions that would be felt more intensely in South Africa and in some frontier market economies.

Various sub-Saharan African countries also face homegrown risks stemming from security threats (Sahel, Nigeria, Mali), political instability (Central African Republic), and adverse climate conditions.

Policy options

Revenue mobilization is important in most countries to contribute to provide sustainable funding for policy priorities. Fiscal policy should also aim at rebuilding buffers in countries where the debt dynamics raise sustainability concerns or that are vulnerable to adverse developments in commodity prices. This target should be pursued by increasing revenue collections, especially by widening domestic tax bases, particularly in low-income countries.

Containing expenditure on subsidies that could be rationalized and better targeted to the poor would also support revenue streams. It is also important to increase the efficiency of public expenditure through a better selection of projects and improved controls on budget execution.

Monetary policies remain generally appropriate; countries where inflation remains high should keep a tight monetary policy stance. Countries facing balance of payments pressures should let their currencies adjust when exchange rate flexibility is not constrained by currency union or other arrangements, and tighten policies elsewhere.

Frontier-market countries need to strengthen their policy frameworks over time to prepare themselves to manage their increasing exposure to global capital flows.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa should also continue to improve their business climates, to attract foreign investment and encourage the domestic private sector. Progress in this area is critical to lay the foundations for economic diversification and for sustainable and inclusive growth.

Background studies

The Regional Economic Outlook also discusses, in two background studies, the drivers of growth in nonresource-rich sub-Saharan African countries and priorities in managing volatile capital flows.

The first paper reviews the experience of six countries that have experienced high growth rates for 15 years but did not base their growth on natural resources—Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda.

This study concludes that increasing sociopolitical stability, improving macroeconomic policies, strengthening institutions, robust and well coordinated foreign aid, and strong investments in physical and human capital enabled those countries to grow at a sustained pace for a prolonged period. These countries’ experience carries useful lessons for their own future and for other low-income countries.

The second study conducts an analysis of the causes, evolution, and macroeconomic implications of capital flows to sub-Saharan frontier markets since 2010 with particular attention to portfolio and cross-border bank flows.

This paper argues that vulnerabilities stemming from the volatility of capital flows can be mitigated by compiling accurate and reliable data; maintaining sound fiscal, monetary and exchange policies; and enhancing the capacity to implement effective macroprudential measures. Any measures to manage capital flows directly should be used with caution.

Government is the #1 enemy of the people and the source of all major problems of humanity. Anarchy is the best political system. Basil Venitis, venitis@gmail.com, http://themostsearched.blogspot.com, @Venitis

0 komentar:

Post a Comment